Crypto-Assets: a new global tax transparency framework

Since the G20 declared the end of bank secrecy in 2009, the fight against tax evasion has been gaining momentum. According to OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann, “in 2021, over 100 jurisdictions exchanged information on 111 million financial accounts, covering total assets of EUR 11 trillion”.

However, unlike traditional financial products, crypto-assets can be transferred and held without using traditional financial intermediaries. The decentralized and pseudonymous nature of the protocols have reduced tax administrations’ visibility on tax-relevant activities carried out within the sector, increasing the difficulty of verifying whether associated tax liabilities are appropriately reported and assessed, despite the transparency nature of the blockchain. In addition, the crypto-asset market has given rise to a new set of intermediaries and other service providers, such as crypto-asset exchanges and wallet providers, which may currently only be subject to limited regulatory oversight.

In this context, the OECD, fearing a loss of effectiveness of the current tools available to tax authorities in terms of exchange of information, particularly in the context of the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), has developed a new tax transparency framework which provides for the automatic exchange of tax information on transactions in crypto-assets in a standardised manner with the jurisdictions of residence of taxpayers. The new tax framework is referred to as the “Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework” or “CARF”.

Who are the entities responsible for collecting and transmitting the information ?

Any individual or entity that, as a business, provides a service effectuating exchange transactions for or on behalf of customers, including by acting as a counterparty, or as an intermediary, to such exchange transactions, or by making available a trading platform, is in the scope of the CARF.

A service effectuating exchange transactions includes any service through which the customer can receive relevant crypto-assets for fiat currencies, or vice versa, or exchange of other relevant crypto-assets. This excludes the activities of an investment fund investing in cryptoAssets since such activities do not permit the investors in the fund to effectuate exchange transactions.

Furthermore, only service providers who carry out operations in the name of or on behalf of their clients and within the framework of their activity (which excludes persons who carry out operations for their own account or individuals or on a very infrequent basis for non-commercial reasons).

What crypto-assets are in the scope of the CARF ?

The CARF has a broad scope as a crypto asset is defined as “a digital representation of value that relies on a cryptographically secured distributed ledger or a similar technology to validate and secure transactions”.

As such, the term crypto-asset includes:

- utility tokens and crypto-currencies (BTC, ETH, MATIC etc.);

- non-fungible tokens or “NFTs” representing rights to collectibles, games, artworks, physical goods etc.;

- stablecoins; and

- other derivatives issued in the form of a crypto-asset.

Three crypto-assets, however, are excluded from the scope of information exchange to the extent that they present limited risks of tax evasion:

- Crypto-assets that the crypto-asset service provider has adequately determined that they cannot be used for payment or investment purposes. Service providers may rely on the classification of the crypto-assets that was made for the purpose of determining whether the crypto-asset is a virtual asset for AML/KYC purposes pursuant to the FATF Recommendations. This excludes crypto-assets that can only be traded or used within a limited network or fixed environment (private blockchains) beyond which they cannot be transferred or traded on a secondary market (e.g., vouchers for books or restaurants, loyalty programs, music or other digital media as well as tickets, data storage etc.);

- Central Bank Digital Currencies, given that “they are a digital form of fiat currency”;

- Specified Electronic Money Products, which represents a digital representation of a single fiat currency issued on receipt of funds for the purpose of making payment transactions represented by a claim on the issuer denominated in the same fiat currency by virtue of regulatory requirements.

The reporting of the latter two categories is ensured under the CRS.

Given this rather broad definition, crypto-Assets covered under the CARF can also fall within the scope of the FATF recommendations. As such, the OECD proposals contain provisions ensuring that the new due diligence requirements can, as far as possible, be built on existing AML/KYC obligations. It also contains provisions to ensure effective interaction between the CRS and the CARF, in particular to limit instances of double reporting, while maintaining maximum operational flexibility for reporting financial institutions that are also subject to obligations under the CARF.

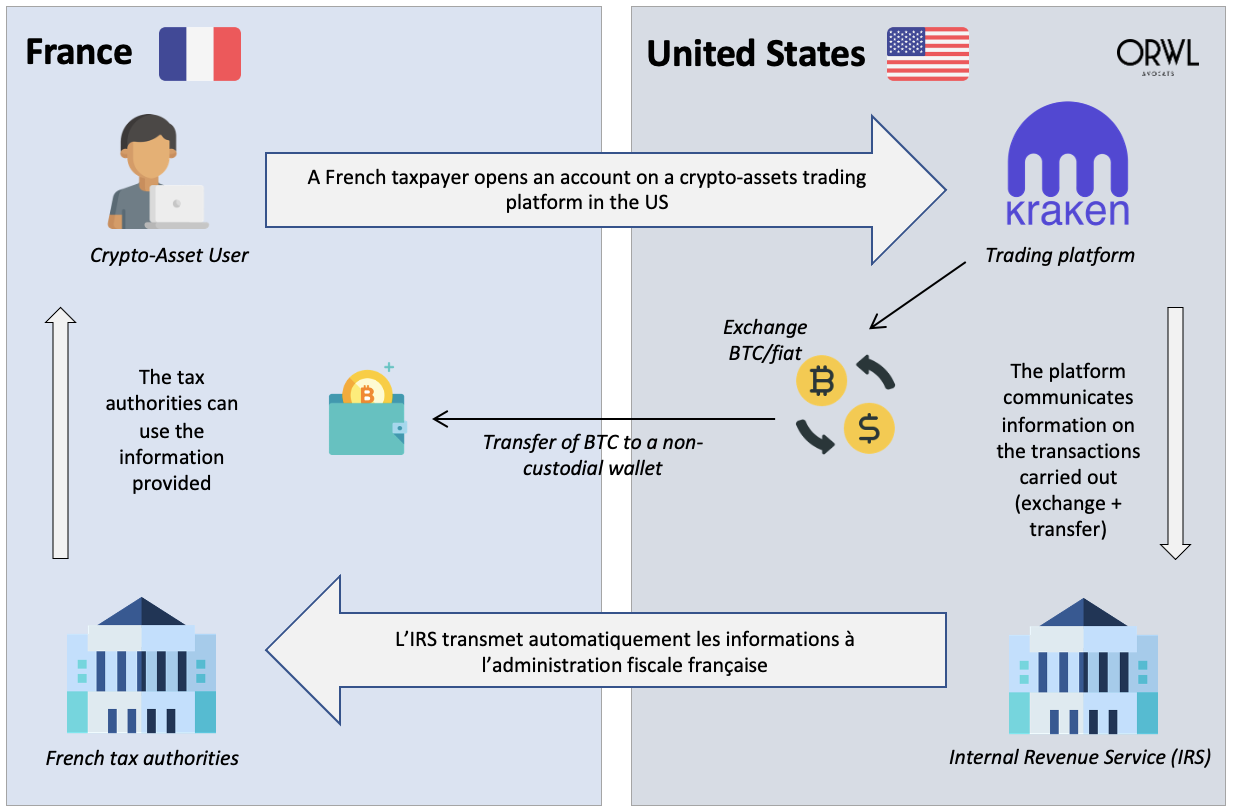

In practice, these new measures will mainly target trading platforms (Binance, Kraken, FTX, etc.) but also intermediaries and other service providers, such as brokers and dealers.

What information should be reported?

Each year, crypto asset service providers (CASPs) will have to report to the relevant tax authorities certain information about users who are tax residents of one of the signatory countries.

In addition to the name, date of birth, taxpayer identification number and jurisdiction of residence of the user, which they will now have to request from their users, the PSCAs will have to report the following information:

- the type of crypto-asset, the aggregate gross amount paid or received and the volume of exchanges between crypto-assets and fiat currencies;

- the type of crypto-asset, the aggregate fair market value and the volume of exchanges between crypto-assets;

- Retail payment transactions for a value exceeding USD 50,000. In this case, CASPs will need to treat the merchant’s customer as a crypto-asset user;

- transfers of crypto-assets (deposit or withdrawal): in this respect, the CASPs will have to specify the value in fiat currencies and the nature of the transfer (airdrop, staking, borrowing, etc.) when it is aware of notably, in the context of the application of its anti-money laundering measures;

- transfers of crypto-assets to an external wallet, unless that wallet is associated with a virtual asset service provider or a financial institution, as defined in the FATF Recommendations. CASPs will be required to collect and retain in their records, for a period of at least five years, all addresses of unhosted wallets with which the user has interacted (deposited from or withdrawn to). While they will not be required to provide the details of these addresses spontaneously each year, this measure is intended to ensure that the tax authorities have access to them on request.

What are the consequences for taxpayers?

The CARF aims to ensure transparency with respect to crypto-asset transactions, in order to allow tax administrations to have access to and exploit information that is still largely inaccessible to them today, in particular when this information is held by foreign actors.

Currently, the only way for the French tax authorities to obtain information on crypto-assets held abroad by a taxpayer is to make a request for information from the taxpayer or through administrative assistance from a foreign tax authority, even though the latter does not necessarily have this information.

With the CARF, the French tax authorities will be systematically provided, through automatically exchanging on an annual basis, with information related to crypto-assets held by a French taxpayer. This cooperation will allow the tax authorities to have timely information that they can exploit, including through algorithms, to make links with the tax returns filed.

They will thus have almost exhaustive information on crypto-account accounts held and crypto-asset transactions carried out via intermediaries by French taxpayers.

It will therefore be necessary to avoid memory loss when reporting, each year, crypto-assets accounts opened abroad and taxable transfers.

New due diligence obligations for service providers

The CARF contains the due diligence procedures to be followed by CASPs in identifying their crypto-asset users, determining the relevant tax jurisdictions for reporting purposes and collecting relevant information needed to comply with the reporting requirements under the CARF. It specifies that CASPs may refer to internal procedures already in place for the purposes of compliance with other regulations.

When?

The CARF contains model rules that can be transposed into domestic legislation, and commentary to help administrations with implementation.

Over the next months, the OECD will be taking forward work on the legal and operational instruments to facilitate the international exchange of information collected on that basis of the CARF and to ensure its effective and widespread implementation, including the timing for starting exchanges under the CARF.

In the same way as for the CRS, a multilateral framework agreement will be signed between the competent authorities and transposed into national law. There is therefore no precise date for the implementation of the measures at this time.

However, like the OECD, the European Union is currently developing a framework for automatic exchange of information on crypto-assets between Member States that could come into effect sooner.